Asma Khan’s saag paneer – spinach with Indian cheese

Eaten with bread or rice, saag paneer makes a satisfying midweek meal. Spinach is one of those vegetables that can be hard to estimate as it reduces dramatically when cooked. As this recipe is a main dish for two adults, I’ve suggested 750-900g of spinach. My personal preference is not to fry the paneer before it is added to this dish, but if you prefer to give it a little colour then follow the frying instructions in the directions.

Serves 2

- fresh spinach leaves 750-900g, washed

- ghee 2 tbsp, melted, or butter or vegetable oil

- shallots 2, finely chopped

- fresh ginger paste ½ tsp

- garlic 2 cloves, crushed

- paneer 100g, homemade or ready-made, cut into 2.5cm cubes

- tomato 1, chopped into cubes

- green chilli 1, cut in half

- ground turmeric ¼ tsp

- chilli powder ¼ tsp

- salt to taste

- double cream or clotted cream 1 tbsp

Bring a large pan of water to the boil. Drop the spinach into the pan and blanch for 20-30 seconds. Using a slotted spoon, remove the spinach from the pan, drain and refresh in cold water. Roughly chop the spinach, then squeeze to remove any remaining liquid – it should be as dry as possible.

In a shallow saucepan, heat the ghee, butter or oil over a medium heat. Add the chopped shallots, ginger paste and garlic, and cook for 2 minutes until they start to colour.

If frying the paneer first: in a non-stick saucepan, heat the oil over a medium-high heat. Add the paneer cubes to the pan in a single layer. Cook, turning the cubes around quickly, to seal on all sides. Using a slotted spoon, remove the paneer cubes from the pan, then place on a plate and set aside.

Add the tomato, green chilli, turmeric, chilli powder and salt. Cook over a medium-high heat for 5-6 minutes. Add the blanched spinach and paneer cubes. Cook, stirring, for a further 3-4 minutes.

Taste to check the seasoning and adjust as necessary. Before serving, pour the cream over the top of the dish.

Nik Sharma’s roasted cauliflower in turmeric kefir

This recipe takes advantage of kefir (buttermilk can be substituted) for its bright acidity. I prefer to use a bottle of freshly opened kefir or buttermilk here, because as these liquids age, the lactic acid increases, which not only leaves a strong tart taste but also causes the milk proteins to curdle quickly on heating.

Using the acidity of fermented dairy such as kefir and the Maillard reaction creates a bittersweet taste and new aroma molecules in vegetables. Chickpea flour, which contains starch, acts as a thickener for the base of the sauce. The sound of the seeds sizzling is a good indicator of how hot your oil is: if the oil is hot enough, they will sizzle immediately and brown quickly.

Serves 4

- cauliflower 910g, broken into bite-size florets

- garam masala 1 tsp

- fine sea salt

- grapeseed or other neutral oil 60ml

- red onion 150g, minced

- ground turmeric ½ tsp

- red chilli powder ½ tsp (optional)

- chickpea flour 30g

- fresh kefir or buttermilk 480ml

- cumin seeds ½ tsp

- black mustard seeds ½ tsp

- red chilli flakes 1 tsp

- coriander or flat-leaf parsley 2 tbsp, chopped

Preheat the oven to 200C fan/gas mark 7.

Place the cauliflower in a roasting pan or baking dish. Sprinkle with the garam masala, season with salt and toss to coat. Drizzle with 1 tablespoon of the oil and toss to coat evenly. Roast the cauliflower for 20-30 minutes, until golden brown and slightly charred. Stir the florets halfway through roasting.

While the cauliflower is roasting, place a deep, medium saucepan or casserole pot over medium-high heat. Add 1 tablespoon of the oil to the pan. Add the onions and sauté until they just start to turn translucent – 4-5 minutes. Add the turmeric and chilli powder and cook for 30 seconds. Lower the heat to medium-low and add the chickpea flour. Cook, stirring constantly, for 2-3 minutes. Lower the heat to a gentle simmer and fold in the kefir, stirring constantly. Watch the liquid carefully as* it cooks until it thickens slightly – 2-3 minutes. Fold the roasted cauliflower into the liquid and remove from the heat. Taste and add salt if necessary.

Heat a small frying pan over medium-high heat. Add the remaining 2 tablespoons of oil. Once the oil is hot, add the cumin and black mustard seeds and cook until they start to pop and the cumin starts to brown – 30-45 seconds. Remove from the heat and add the chilli flakes, swirling the oil in the pan until the oil turns red. Quickly pour the hot oil with the seeds over the cauliflower in the saucepan. Garnish with the chopped coriander and serve warm with rice or parathas.

Vivek Singh’s pork vindalho

Vindalho – or vindaloo – is possibly one of the most recognised and loved curries in the world. Even so, as much as it’s loved, it’s also a mystery. For most Indians, it is a hot and spicy dish that must contain potatoes (aloo in Hindi) and no doubt you will come across recipes with potatoes as well. Please don’t be disappointed that this recipe doesn’t list potatoes. It’s the real McCoy, true to its Portuguese origins. This Goan curry is unique for being intense, rich, sharp, hot and sweet at the same time.

Serves 5-6

- pork shoulder 750g, cut into 2.5cm pieces

- vegetable or coconut oil 4 tbsp

- black mustard seeds 1 tsp

- red onions 500g, finely sliced

- tomatoes 5, ripe, chopped

- small green chillies 2, stalks removed

- curry leaves 10

- jaggery or palm sugar 1 tbsp

- salt 1½ tsp

- tamarind pulp 2 tbsp

- small sweet pickled onions 6, each cut into 2

- fresh green coriander 20g, finely chopped

For the paste

- cinnamon stick 5cm

- cardamom pods 6, crushed

- black peppercorns 1 tsp

- cloves 10

- cumin seeds 1 tsp

- coriander seeds 1 tsp

- ground Kashmiri chilli powder 2 tbsp

- ground turmeric ½ tsp

- garlic 10 cloves

- ginger 5cm piece, peeled

- malt vinegar 60ml

Grind together the paste ingredients, starting with the largest spices first, then adding the cumin and coriander seeds, and blend to a fine consistency. Add the chilli and turmeric powders and mix well. Add the garlic and ginger and grind, adding the vinegar to make a paste.

Rub the paste into the diced pork and leave to sit for at least an hour or overnight in a refrigerator.

Heat the oil in a wide, pan (one that has a lid) over a medium-low flame, add the mustard seeds and let crackle for 30 seconds. Add the onions and fry until soft and golden. Add the tomatoes, chillies and curry leaves, and cook until the tomatoes start to break down.

Add the pork and turn the heat up to medium-high. Cook for 10-12 minutes stirring continually until the pork browns. Add 250ml of water, stir well, add the jaggery, salt and tamarind and mix through. Bring to a simmer, cover tightly, turn the heat right down and cook gently for 45-60 minutes.

Check the amount of liquid in the pan and, if needed, cook for another 15 minutes, or until the meat is very tender and the sauce has thickened.

Scatter the pickled onions and chopped coriander over the dish and serve hot.

The leftover curry tastes even better the next day.

Rukmini Iyer’s lime and coconut dal

This dal is based on one that my mother makes, with fresh coconut chunks and bright yellow chana dal. Chana dal has an exceptionally nice texture and flavour, but requires soaking and a long stint in the pan, so this version substitutes the quicker cooking Egyptian red lentils. Roopa Gulati, another honorary food mum, introduced me to the lime element – hands down, I can say this is my favourite dal.

Serves 2

- *red lentils8 140g, rinsed

- ground turmeric 1 scant tsp

- coconut milk 1 x 400ml tin

- fresh coconut pieces 90g, cut into 1cm cubes

- boiling water 200ml

- garlic 1 clove, unpeeled

- onion 1, thinly sliced

- ground cumin 1 tsp

- oil 1 tbsp

- baby leaf spinach 3-4 big handfuls

- limes juice and zest of 2

- sea salt flakes to taste

To serve

- freshly cooked rice

- naan bread of chapatis

- lime wedges

Preheat the oven to 180 fan/gas mark 6.

Tip the lentils, turmeric, coconut milk, coconut pieces, boiling water and garlic into a small roasting tin or lidded casserole dish. Mix the onions, cumin and oil on a chopping board, then scatter them over the lentils. Cover tightly with foil or a lid, then transfer to the oven and cook for 45 minutes.

As soon as the dal is cooked, stir through the baby leaf spinach until it has just wilted. Adjust the texture to your preferred consistency with a little boiling water. Stir in the lime juice and zest, taste and adjust the salt, and serve with rice, naan bread or chapatis and extra lime wedges for squeezing.

Note: you can find fresh coconut pieces in little packets in the chiller cabinet at the supermarket, next to the cut-up pineapple and melon, which I find easier than chopping up a whole coconut for such a small quantity.

Kaeng khiao wan – Thai green curry by Wichet Khongphoon

The Thai name for green curry literally means green and sweet curry. Although green curry is one of the most famous Thai dishes, little is known about its historical origins. One of its first mentions was in the early 1900s by Khun Ying Plien Plassakornwong, a sort of Thai Mrs Beeton. She was a lady-in-waiting at the royal palace in Bangkok and compiled the first comprehensive cookbook of Thai recipes. The green colour is derived from green chillies, introduced to Thailand by early Portuguese traders.

My own culinary interests focus on food from the south of Thailand, where traditionally, you will find green curry made with goat and served with roti. At Supawan, we did not have green curry on our menu until my mum came to visit a few years ago. She reminded me of the right proportion of spices and fresh ingredients – also adding turmeric into the paste to give the curry a vibrant green colour. I hope my Thai green curry recipe will bring you warmth and help lift your spirits in the coming months.

Serves 4

For the curry paste (makes about 1kg, freeze any not used for this recipe)

- large green chillies 700g

- coriander seeds 4g, ground and toasted

- cumin seeds 6g, ground and toasted

- black peppercorns 6g, ground and toasted

- fresh galangal root 30g, chopped

- lemongrass 50g, chopped

- makrut lime zest 15g

- garlic 70g, chopped

- shallots 130g, chopped

- fresh turmeric, 70g chopped

- small hot green chillies 20g

- shrimp paste 20g (optional)

For the curry

- makrut lime leaves 3

- vegetable oil 60g

- curry paste 200g (see before)

- coconut milk 500g

- salt 2g

- palm sugar 50g

- chicken stock 250g

- chicken fillets 500g, sliced across into thin strips

- purple aubergines 1½, cut into quarters

- pea aubergines 100g, washed with stems removed (or use baby corn or bamboo shoots)

- green beans 100g, cut in half

- Thai aubergines 4, cut into quarters

- fish sauce 45g

- Thai holy basil 5 sprigs

- red bird’s eye chillies 5, for garnish

I advise you to not wear any white clothes while making this recipe, and start by turning the kitchen fan on high. Make sure you’ve prepared all ingredients before starting to make the curry, as it moves quickly.

First, make the paste. Normally, in Thailand, the ingredients are pounded by hand using a stone pestle and mortar, but I recommend taking advantage of modern convenience and saving yourself some time by using a hand-held electric blender. Blitz all the ingredients until well blended.

For the curry, fry the makrut leaves in hot oil for a minute. Keep stirring and don’t let them burn.

Add the curry paste, stirring at a brisk pace until it starts to split into oil and smells fragrant, about 1-2 minutes. Pour in half of the coconut milk and keep stirring to prevent it from sticking to the bottom of the pan and burning.

Reduce the sauce by a third until a lovely oil starts to form on the top. Turn up the heat to high, season with salt, palm sugar, the rest of the coconut milk and the chicken stock, and bring to a boil.

Add the chicken and cook for about 5 minutes. Add the purple aubergine pieces and cook for 1-2 minutes, then add the rest of the vegetables. Cook for about 2 more minutes, until the vegetables are cooked, but retain their crunch. Add the fish sauce, taste, then garnish with Thai sweet basil leaves and red chillies.

Aloo gosht – Punjabi mutton and potato curry by Sumayya Usmani

My mother’s family come from Pakistani Punjab, where flavours are simple and no meat stew is cooked without a vegetable. This is a land of agriculture and seasonal produce, and the simplicity of this dish is not a failing, but a celebration of what the land provides (without it being masked by spice). Aloo gosht is so revered in Punjab that poetry has been written about it. This recipe has been passed on by my mother’s cousin, Tanveer Khala, and has graced many family meals.

Serves 4-6

- vegetable oil 50ml

- red onion 1 large, finely chopped

- ginger 1cm piece, peeled and grated

- garlic 2 cloves, minced

- mutton 1kg with bone, cut into 5-6cm chunks

- salt 1-2 tsp

- ground turmeric ½ tsp

- paprika 1 tsp (not smoked)

- red chilli powder 1 tsp

- water 250-450ml

- vegetable oil 3-4 tbsp

- tomatoes 2 medium, finely chopped

- coriander seeds 1 tsp, dry-roasted and ground

- maris piper potatoes 500g, peeled and quartered

To garnish

- garam masala 1 tsp

- coriander leaves 2 tbsp, chopped

- green chillies 2, finely chopped

To serve

- plain basmati rice or naan bread

Heat the oil in a large saucepan with a lid over a medium heat. When hot, add the onions, ginger and garlic and cook for 7-8 minutes until the onions are light brown. Add the mutton pieces, salt, turmeric, paprika and red chilli powder then add 150ml water and reduce the heat to medium low. Cover the pan with the lid and cook for about 15-20 minutes until the mutton is tender and the curry is reddish brown, checking the water has not dried up – if it does add about 4 teaspoons of water to ensure that the mutton is just covered.

Increase the heat to medium high, add the vegetable oil, tomatoes and ground coriander seeds. Stir-fry to allow the oil in the pan to cook through the tomatoes and create a thick red sauce with oil separating and rising to the surface of the curry.

Add the potatoes and 200-300ml water, depending on how watery you prefer the curry (traditionally it is quite watery), then reduce the heat to medium low and continue to cook for 10-15 minutes until the potatoes are tender. The curry should be red, with oil rising to the surface, but watery. If this has not happened yet, keep the saucepan on a very low heat for a further 5-10 minutes, but make sure not to overcook the potatoes.

Turn off the heat, cover with the lid and let the curry simmer in its own heat for about 10 minutes before serving. When ready to serve, transfer to a serving dish and garnish with garam masala, chopped coriander and chopped green chillies. This is best served with plain basmati rice or naan bread.

Andi Oliver’s curried coconut chickpeas and maple roast spiced winter ground provision

There are so many ways to serve this dish. Keep it vegan like this and throw together a crisp green salad, or sauté some lovely seasonal wild mushrooms in garlic and toss them on the top. Or you could add a poached egg, or a grilled lamb chop, or a pan-fried piece of fish and a poached egg, or some fried halloumi or plantain. There really are seemingly endless possibilities.

Serves 4-5 people

For the coconut curried chickpeas

- white onion 1 medium, thinly sliced

- garlic 9 cloves, blitzed together with a little oil to a puree

- scotch bonnet chilli ½ (or 2 whole bird’s eye chillies) finely chopped (adjust according to how hot you want it, ie a whole scotch bonnet will be very hot in this ratio, ½ will give you medium heat, 1 bird’s eye will be mild, 2 will be medium to high heat)

- whole green cardamom pods 5g

- whole star anise 3g

- whole allspice 5g

- whole cloves 2g

- cinnamon stick 8g

- chickpeas 2 x 400g tins, drained

- bay leaves 2

- coconut milk 1 tin

- chicken stock 250ml (or vegetable stock to keep it vegan)

- baby spinach 100g

For the roast spiced ground provision

- parsnip 150g, diced

- sweet potato 150g, diced

- pumpkin 150g, deseeded and diced

- celeriac 150g, diced (keep the diced vegetables in a bowl of cold water with the juice of a lemon to stop them going brown)

- curry powder 15g (any kind – I used Caribbean but any that you favour will do)

- ground cumin 5g

- ground coriander 5g

- ground turmeric 5g

- maple syrup 50ml

- salt a pinch

For the green dressing

- fresh coriander 20g

- flat-leaf parsley 20g

- spring onions 2

- garlic 2 cloves

- lime juice of 1

- cold-pressed rapeseed oil 200ml

- maple syrup 5ml

- salt a pinch

Preheat the oven to 150C fan/gas mark 3½. For the curried chickpeas, gently soften the onion and garlic until lightly golden, add the scotch bonnet (or chilli of choice) and soften for around 4 minutes or so.

Grind all the chickpea spices (except the cinnamon stick) in a pestle and mortar or spice mill and tip them into the onion mix. Add the cinnamon stick and lightly sauté over a low heat stirring intermittently and very gently for 10 minutes.

Add the chickpeas, bay leaves, coconut milk and stock, and simmer for 30 minutes stirring very gently and occasionally – you just want to make sure it’s not sticking to the bottom. If it’s getting too thick splash in a little more stock. You want the mix to flow quite freely with a good amount of sauce and not become too claggy.

After 30 minutes add the baby spinach and stir through.

For the ground provision, parboil all the diced vegetables in a large pan of boiling salted water for about 7 minutes, drain immediately, leave to cool for 15 minutes and transfer to a roasting tin. Stir through the spices, add a liberal splash of rapeseed oil, sprinkle with good sea salt, and slip into an oven for 35-40 minutes until they have a nice crust on them.

Add the maple syrup and stir through. Return to the oven at 170C fan/gas mark 5 and blast for a further 15 minutes.

Lastly, blitz together the green dressing ingredients in a food processor with a sprinkle of salt and transfer to a bottle or jar.

To serve, spoon a third of the roasted roots into the pot of curried chickpeas and gently stir through. Ladle the curry on to a big serving platter or plate. Spoon the rest of the roots into the middle, then drizzle the green dressing around the dish.

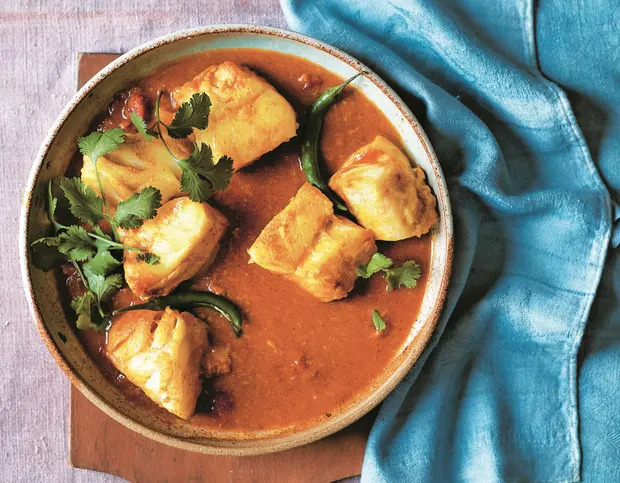

Asma Khan’s macher jhol – Bengali fish curry

In Bengal, the fish used for this recipe would be rohu, a local carp, which requires some skill to debone. At a large family gathering, it makes sense to use fish that has been filleted to make things easier for both you and your guests. If you can source a good mustard oil, it gives this dish a wonderful flavour.

Serves 6 as a main course or 12 as part of a multi-course meal

- fish fillets 1.5kg, such as cod or halibut, skinless, boneless

- salt 3 tsp

- ground turmeric 1½ tsp

- vegetable oil or mustard oil 6 tbsp

- white onion 1 large, finely grated

- garlic 4 cloves, crushed

- ginger 2.5cm piece, crushed to a paste

- ground coriander 1 tbsp

- ground cumin 1 tsp

- chilli powder 1 tsp

- tomato puree 3 tbsp

- tomatoes 200g, cut into 2.5 cm cubes

- warm water 600ml

- sugar ½ tsp

To garnish

- green chillies

- fresh coriander a few sprigs

Cut the fish fillets into 12 equal portions. Mix 1 teaspoon of the salt and 1 teaspoon of the turmeric, then rub on all sides of the fish and set aside for 30 minutes.

In a shallow saucepan, heat 5 tablespoons of the oil over a medium-high heat. If you are using mustard oil, heat the oil until it is smoking hot – this removes its bitter pungency – then bring it down to a medium-high heat. Add the fish to the pan and fry to seal each piece, but do not let the fillets cook through. Remove from the pan to a plate and set aside.

Add the onion, garlic and ginger to the pan and cook, stirring, for 2 minutes over a medium-high heat. If the paste is burning or sticking to the base of the pan, add a splash of water. Add the remaining salt and turmeric, followed by the coriander, cumin, chilli powder, tomato puree and diced tomatoes. Pour in the warm water and cook for 5 minutes. Let the liquid reduce for 15 minutes or until the oil comes to the surface and seeps to the sides of the pan.

Gently return the fish fillets to the pan and cover with the gravy, ensuring all sides of each fillet are cooking evenly. If possible, cook the fish fillets in a single layer in the pan as this will prevent them from breaking up into flakes. Lower the heat, add the sugar and cook, covered, until the fillets are cook through – this should take no longer than 5 minutes.

To serve, garnish the fish with whole green chillies and sprigs of fresh coriander leaves.

Kay Plunkett-Hogge’s gaeng massaman – massaman curry

This is probably the most complex of the Thai curries to make. While there are acceptable massaman pastes available to buy, it’s worth the effort to make from scratch because all the subtle fragrances of the freshly ground spices vanish if the paste sits around for too long.

Its complexity stems from the fact that the dish is not initially Thai. It either came to Thailand with spice traders in the Muslim south of the country, or (and this is my preferred story) it arrived at the court of Siam with the first Persian envoys in the 17th century.

Most commonly, you’ll find it made with beef or chicken. I find it works beautifully with goat, and so I’ve used that here.

Serves 4-6

For the paste

- Thai shallots 4 (or 2 regular shallots)

- garlic 4 cloves

- coriander root 1

- long dried chillies 12

- cinnamon stick 1

- cumin seeds 1 tbsp

- coriander seeds 1 tbsp

- sea salt a pinch

- cloves 2

- cardamom seeds of 1 pod

- black peppercorns ¼ tsp

- lemongrass 2 sticks, bashed and finely chopped

- nutmeg ¼, grated

- kapi (shrimp paste) 1 heaped tbsp

For the curry

- ghee 2 tbsp

- goat meat 400g, cubed

- vegetable oil 2 tbsp

- Thai shallots 4, peeled (or 2 regular shallots, peeled and halved)

- new potatoes 4, halved

- coconut cream 2 tbsp

- coconut milk 1 x 400ml tin

- raisins handful (optional)

- water 200ml

- tamarind paste 2 tbsp

- cardamom pods 6, broken open

- palm sugar 1 tbsp

- nam pla (fish sauce) 1-2 tbsp

- roasted peanuts 1-2 tbsp

To make the paste, preheat the oven to 180C fan/gas mark 6.

Wrap the shallots, garlic and coriander root tightly in tin foil and bake in the oven for about 20 minutes, or until soft.

Meanwhile, in a dry frying pan, toast the dried chillies until they are crispy, shaking them in the pan to ensure they don’t burn. Set aside to cool, then snip them up into small pieces with scissors, discarding the stalks and the seeds. Soak the pieces in warm water for at least 20 minutes. Dry them thoroughly with paper towels.

Toast the cinnamon stick, cumin seeds and coriander seeds in the dry pan until they’re fragrant. Then grind the paste, starting with the dried chillies and the salt, followed by the toasted spices, the remaining dry spices, and the lemongrass. Peel the shallots and garlic, cut the coriander root into small pieces, and pound them into the paste, followed by the grated nutmeg and the kapi.

Keep grinding until the paste is as smooth as possible, and everything is thoroughly incorporated.

To make the curry, melt the ghee in a large frying pan, and gently brown the meat. You will need to do this in batches.

Heat the vegetable oil in a large wok or saucepan, then add the paste, and fry until it’s very fragrant. Add the meat, shallots, potatoes and the coconut cream, and stir them thoroughly into the paste. Then add the coconut milk, raisins (if using) and water, bring up to the boil, and simmer for 30 minutes.

Now add the tamarind paste, cardamom, palm sugar and nam pla and gently simmer, partially covered, for another 30-40 minutes, until the meat is tender. About 10 minutes before you finish cooking, add the peanuts.

Finally, taste the curry and adjust the seasoning. You’re looking for a sour start to its taste, which then develops in the mouth to become sweet and savoury.